ASK farmers what they worry about most, generally they'll say water or rainfall.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

Growing up on her family's farm at Tambellup, Prue Batchelor has seen first-hand how much water and rainfall plays on farmers' minds, which is why she made it the premise of her landscape architecture Masters degree thesis, conducted through the University of Melbourne.

Titled 'Give a Dam', Ms Batchelor sought to improve water availability for farmers by rethinking the concept of traditional dams on farms.

She said salinity was a major problem for Great Southern farmers, preventing most from accessing the abundance of groundwater as it was too salty.

As a result most farmers in the Great Southern (as well as other regions) rely on rainfall and although a lot of these areas are considered higher rainfall, farmers are wary that growing season rainfall has been decreasing and becoming more variable.

Already having an understanding of agriculture, coupled with her learned knowledge of landscape architecture, Ms Batchelor blended two disciplines to come at the issue from a new perspective, thereby proposing three interventions over different times, while maintaining farm productivity.

Retrofitting existing dams:

"The main issue with dams is the amount of water that is lost to evaporation each year and I looked at a range of covering options," Ms Batchelor said.

While dam covers are not very common on farm dams in Australia yet, Ms Batchelor expects this to change.

"The cover I went with is not new but relatively new to Australia (Hexa-Cover, a Dutch company now being produced in Victoria), they are recycled plastic discs that float on the dam but don't get blown away and can reduce evaporation by 90 per cent.

"There's no additional infrastructure required, so it's an easy, quick application."

But for this option to be effective, there needs to be water in the dam, which relies on rainfall and run-off.

"So I looked at the roaded catchment drains that exist in all the dams in the region and how to make them more effective because small amounts of rain often don't reach the dam because the flow rates aren't high enough," she said.

"I looked at covering road catchments with an impermeable membrane (ie. plastic), which I was hesitant about because the idea of putting plastic onto a paddock didn't sit well with me, but the more I looked at it and the way that you can use recycled plastic from old grain bags and being able to lay that as a surface so run-off goes into the dams - it made sense."

But Ms Batchelor wanted to further enhance these catchments to maximise the benefit of having plastic on the ground.

"This involved looking at the topography of the landscape, vegetation and livestock in those specific paddocks and being able to capitalise on fencing off those catchments, which are not utilised by livestock anyway or cropping, so farmers are not losing arable land," she said.

Ms Batchelor said vegetation was important for two reasons: to improve the aesthetics of having a big plastic sheet in the paddock and the use of endemic species allows for greater environmental sustainability by creating habitats for birds and corridors of enhanced biodiversity of the area.

"This will help improve the soil and ensure that groundwater salinity stays at bay," Ms Batchelor said.

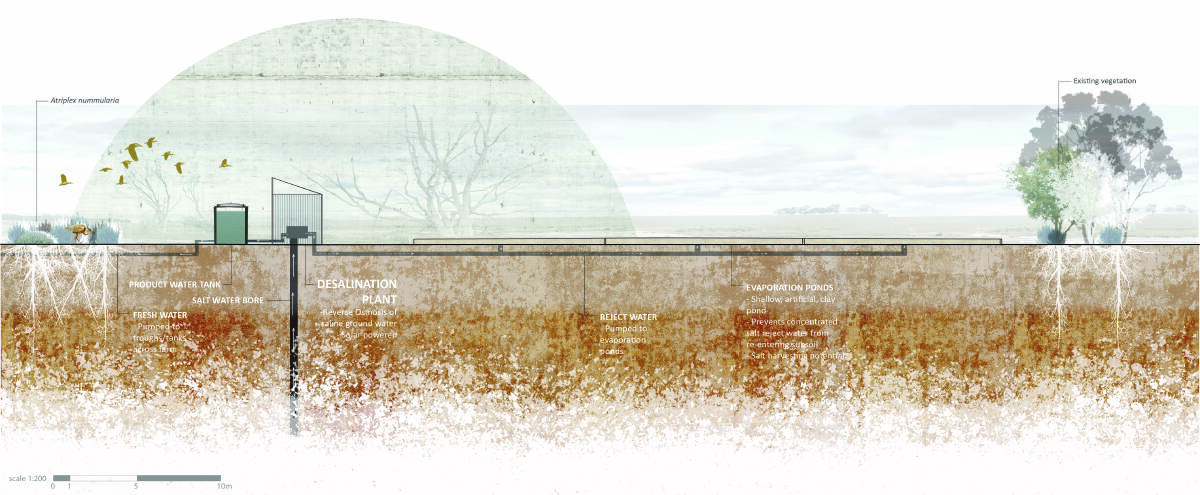

Desalination plant:

Ms Batchelor said this option was about "working with what you've got - you've got salt in the landscape and so much groundwater but it's salty, so it's about being able to utilise it".

"This option ensures you have a climate independent freshwater source, but the reject water is the by-product of the process and is incredibly saline and needs to be deposited in a safe place," she said.

"The design intervention I proposed was to build a really shallow dam and it works as an evaporation pond, so you put that saline by-product into it and the water evaporates and you end up with salt - which could be another commodity for farmers and could diversify their operation."

Although it requires a high capital investment, Ms Batchelor said establishing a desalination plant ensures greater longevity of a farm.

She estimated it would take about five to seven years for growers to start seeing returns on their investment.

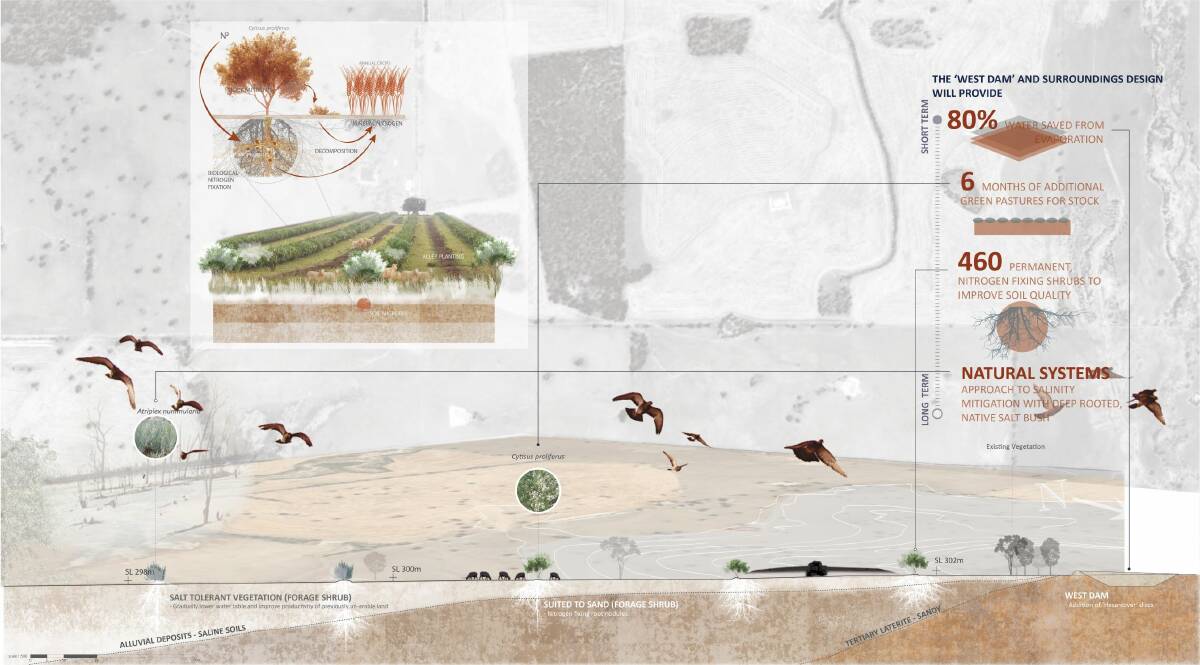

A long-term commitment to improved farm systems:

This intervention is about reworking surface and groundwater relationships on the farm more broadly while being functional for cropping and livestock operations and not interfering in productivity.

"Rather than viewing each farming process separately, it's integrated into one system," Ms Batchelor said.

It involves planting vegetation such as saltbush and Tagasaste, which are good as a summer feed for livestock, being planted in alleys at 45 metre increments so cropping practices are not impacted.

"These alleys are along the contours and take up minimal arable land, but those plants are deep rooted, which keeps the ground salt at bay and will also prevent flooding or water logging further downstream into the already salt-scolded gullies," she said.

"This is a long-term integrated intervention, where farmers are looking at their farm, landscape and soil as one system rather than separately.

"Being able to diversify how farmers work with their landscape will strengthen it, ensure productivity and enhance it in the long-term."

This intervention would use dams with covers but Ms Batchelor said it was also more about capturing any spill away water and what happens below the dam with excess run-off (if there is any) and maximising it in the best way possible.

Determining whether intervention one or two to implement would depend on the individual farm and the landscape, but she said these were essentially typologies/ methodologies that could be adopted.

"Farmers have the onground knowledge of their properties, they are just missing the design aspect, which is where farming and landscape architecture can come together to work out what suits each farm," she said.

- More information: phone Prue Batchelor on 0477 128 756.