A PROJECT which aims to build the capacity for small exporters in Australia to exploit new breeding technologies (NBT) was the focus of a webinar hosted by Murdoch University and the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications late last month.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

The project is funded by the Federal government and forms part of a wider Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment program, called Package Assisting Small Exporters.

The webinar attracted 632 participants from more than 40 countries, who tuned in to learn about the forward looking project, which primarily aims to enable the Australian grains and horticultural industries to be first-movers in applying NBT, such as SDN-1, to crop improvement.

The project will provide information on new science and technologies, as well as on the policies and regulations that relate to them both in Australia and with trading partners.

Speaking during the webinar, WA State Agricultural Biotechnology Centre director Michael Jones said Australia was a food exporting nation and in order to stay relevant, the debate on gene-edited crops needed to move forward and a clear path to market developed.

"Out of the top 10 countries that Australian wheat was exported to between 2016 and 2020, eight were from South East Asia and in total those 10 countries were responsible for 70 to 80 per cent of wheat that Australia exported, totalling $4.6 billion in trade," professor Jones said.

"For barley over the same period, six of the top 10 countries are in South East Asia and the value of the top 10 is $1.6b a year.

"For canola, our major export destination is the European Union, but after that the rest goes to China, Japan, Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates, Nepal and Malaysia.

"Canola is interesting as in this particular case, those exports include genetically modified canola (GM) - about 25pc of the Australian canola is GM and in WA that is a bit higher at 35pc."

Add Australian fruit and vegetables to the list - 77pc of which goes to South East Asia - and the importance of the region to Australian agricultural trade is clear.

However, Australia is an ancient and weathered continent and that presents challenges to crop production.

Grain and cereal crops are often water limited with poor soil nutrients and suffer from drought and heat stress.

Professor Jones said for Australia to stay competitive in the export market, we need to apply the best science and technology to improve yields and quality and that includes gene editing.

"In a conventional breeding program, a beneficial gene from a wild relative is crossed with a cultivar and after F1 generation it is backcrossed to produce a new cultivar, but due to linkage drag there are unwanted genes transferred as well, so it's not very precise," he said.

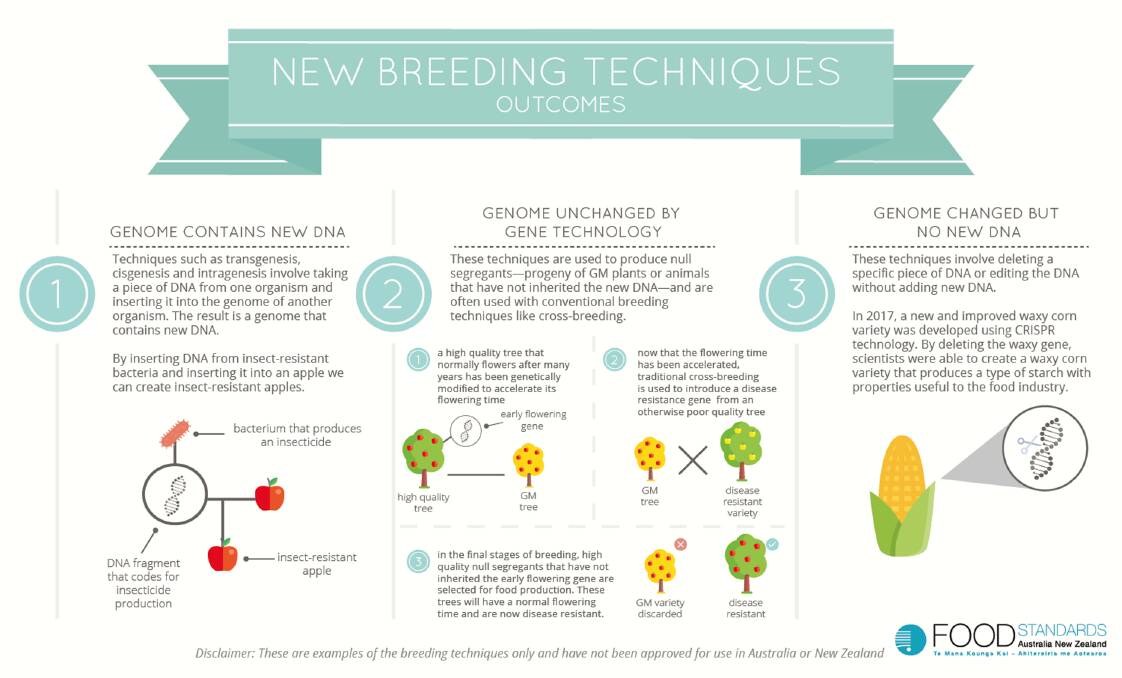

"With transgenesis, cisgenesis and intragenesis, the methodology is exactly the same but they refer to slightly different genes - transgenesis from unrelated organisms, cisgenesis from related species and intragenesis from genes or components of genes from the same species.

"In the past decade, gene editing has come on in leaps and bounds - it now involves targeted mutagenesis through techniques such as SDN-1, that create specific and targeted changes in the variety."

Conventional cross-breeding is defined by the Australian Gene Technology Act as genetic manipulation, but it is excluded from the regulations and with that, back crossing is usually required, but it is transgene free.

Mutation breeding involves random mutagenesis and many breaks across the genome and takes eight to 10 years, but again doesn't involve transgenes.

Transgenic breeding is the introduction of traits from other organisms and as external DNA is integrated it is subjected to GM regulations which often extends the time to market.

Genome editing is a newer technique, which differs from GM and involves targeted mutagenesis, meaning backcrossing is not required and it can speed up the process of the path to market.

Professor Jones said the power of SND-1 gene editing for crop improvement had already been well established.

"In one example for wheat, the gene-editing of all six MLO (Mildew Locus O) alleles in hexaploid bread wheat offers heritable, broad-spectrum resistance to powdery mildew," he said.

"The MLO gene is a gene for susceptibility to powdery mildew and if all six copies of the MLO gene are mutated, then you get resistance to the damaging barley disease.

"In another example, gene edited triple-recessive mutations altered seed dormancy in wheat, so through SDN-1 the grains in the head were altered to prevent pre-harvest sprouting, which otherwise reduced grain quality and value."

When it comes to regulations in Australia, living organisms are regulated by the Gene Technology Act and administered by the Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (OGTR)

In 2019, SDN-1 technology was deregulated by the OGTR, however food products are regulated by Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ).

SDN-1 is still under view by FSANZ and will go out to public comment mid-year, however the statutory authority will consider individual applications for commercial gene edited products at the moment.

"Most of North and South America have deregulated SDN-1 crops, as have South Africa, Australia and Japan," professor Jones said.

"In other countries, including most of South East Asia, there are ongoing discussions with recommendations to deregulate SDN-1 crops, while in New Zealand and most of Europe, gene edited crops are still regulated as GM crops."

Argentina is probably the most advanced country when it comes to gene editing regulations.

They have five years' experience of gene edited products and have found that there is much faster development from bench to market than what there has been for GM products.

"GM crops have been deregulated in Argentina over the past 20 years and in that time, 90pc were from foreign multinationals and only 8pc from local companies and public research," professor Jones said.

"Whereas for gene edited crops, which have been deregulated for five years, 59pc were from local companies and public research, with only 9pc from foreign multinationals.

"If deregulated, GE has the power to absolutely democratise the technology, so that many public organisations, research institutions and smaller companies can use it to improve more diversified traits and crop species."

However in order for that to become a reality in Australia, FSANZ needs to accept SDN-1 gene edited food with no external DNA as non-GM.

Furthermore, that cannot include an additional tier of regulations for gene-edited crops and products, in other words SDN-1 crops and food need the same regulatory treatment as conventional breeding.