IN Australia, less than one per cent of traditional produce is commercialised for Aboriginal interests, creating a huge barrier to indigenous involvement in the native bush food supply chain.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

Include the fact that Aboriginal people were excluded from having any form of commercial business rights until the 1970s and you end up with multiple generations of people who lack business and entrepreneurial skills, as well as face trying to enter an industry that has started to become oversaturated.

Australian Venture Consultants partner Russell Barnett said the native bush food industry provided a great opportunity for Aboriginal people to build businesses around products that matter to them, creating a connection to country and culture.

However, he said that was tough to do when they were trying to enter a market against companies that were branded as Aboriginal businesses but weren't.

"There's a capacity building issue in terms of developing entrepreneurship and business skills that is a result of two centuries of policy that has denied Aboriginal people the opportunity to establish an entrepreneurial class, which is a problem for many indigenous businesses generally, not just traditional produce," Mr Barnett said.

"While we're making huge progress in that and the number of indigenous-owned businesses in general is growing quite rapidly across Australia, in the native produce industry Aboriginal people face further issues as they are going into markets where there is existing competition that is branded as an indigenous product but it is not owned or run by indigenous people.

"Generally that competition has better access to capital and business skills than indigenous parties do, which puts those indigenous businesses at even more of a disadvantage."

The beginning of a project from Food Innovation Australia Limited (FIAL), an industry-led and Federal government-funded initiative marked a significant step in a national effort to push for more Aboriginal involvement in the bush foods sector.

FIAL engaged the Noongar Land Enterprise Group (NLE), an Aboriginal-led grower group based in Western Australia, to consult around Australia on the native produce industry.

As part of that project, NLE conducted workshops with Aboriginal corporations and people about why the participation rate was so low and what the best way to go about fixing that could be.

FIAL managing director Mirjana Prica said having NLE onboard was the obvious choice as they wanted the solutions derived from the project to be Aboriginal driven.

"One of the key reasons we engaged NLE is that we want Aboriginal people to come back to us with how to solve the situation and what the model for moving forward is," Ms Prica said.

"Typically in the past, non-Aboriginal people have come in and told Aboriginal people how to solve the problems, but we knew in order for this to be successful, those solutions had to come directly from Aboriginal people."

Key members from NLE spoke with as many traditional owners groups as they could to provide the Federal government with confirmation of the Aboriginal sacred knowledge on bush produce.

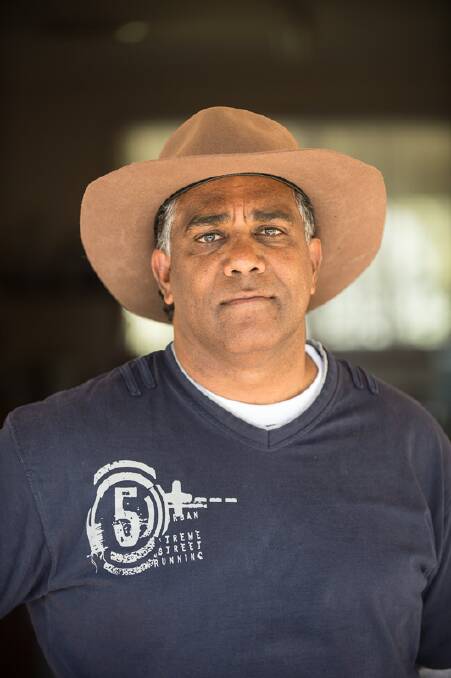

Chairman Oral McGuire said they completed a comprehensive number of road trips and while the workshops were hampered by COVID, they tried to get a good cross-section and met with groups in each State, except Tasmania, but they were represented at a number of workshops on the east coast.

"The idea was to listen to what other groups were interested in, hear stories about their struggles, the opportunities and benefits of what they've already pursued and the challenges they've been confronted with in developing any commercial products in the bush produce industry," Mr McGuire said.

"There were challenges that were consistent with all of us, with the protection of Aboriginal intellectual property and sacred knowledge the key talking point, especially when it came to the complexities of how we protect that as Aboriginal people in a commercial sense.

"Capital raising for ventures and initiatives was also a key issue raised, particularly the cost associated with getting people out on country, especially in remote areas.

"Everyone had ideas, everyone had thoughts and everyone certainly had aspirations and dreams of participating in their own way in the bush produce industry."

As a separate part of the project, NLE has also completed a business case for an indigenous incubation hub focused on bush foods at Avondale Farm, near Beverley, which is owned by the National Trust of Western Australia.

"The business case and feasibility study are proving that there is a massive scope for an initiative like an enterprise hub," Mr McGuire said.

"It's an attractive initiative not for Noongar people in the South West, but for Aboriginal people in all of our regions to embark on.

"The business case is compelling that it is enormously viable and can therefore be enormously successful."

The barriers to indigenous involvement in native produce is not an issue unique to Australia, which was part of the reason behind the creation of the United Nation's Nagoya Protocol in 2010, linking genetic resources to traditional knowledge of indigenous people.

The protocol allows for genetic resources to be held as the property of indigenous people and requires signatory countries to legislate or at least put in place administrative policies in accordance with that.

"Basically it puts in place a framework whereby indigenous people of signatory countries should share in the benefits of the commercialisation of traditional knowledge that's embedded in genetic resources," Mr Barnett said.

"It also states that non-indigenous organisations which are commercialising those genetic resources should get prior informed consent from the traditional owners."

The intellectual property which is recognised when it comes to genetic material is not so much the product itself, but the traditional knowledge that applies to the cultivation and natural harvesting of a species by traditional methods, the processing of that product by traditional methods and its use as a food, medicine, etc.

"Under a strict interpretation of the Nagoya Protocol, if an indigenous group were using a native species for a specific purpose prior to colonisation, they have certain rights to that species," Mr Barnett said.

"So businesses should not be commercialising those products without the consent of the traditional owners and there should be a negotiation of some sharing of the benefits and profits."

While Australia signed the Nagoya Protocol in 2012, it still hasn't been ratified, so there is no legislative protection for indigenous people in the area of genetic resources, which includes traditional produce and native bush foods.

It has been recognised that the majority of businesses producing bush foods in Australia have not intentionally disregarded Aboriginal people, but that does not change the fact that many companies have commercialised native plant species in Australia and sell them without benefit to indigenous groups.

However, there is also a generation of new traditional produce businesses which have started that do have some sort of relationship with indigenous parties.

Those businesses may have some indigenous branding in terms of art which they've acquired the licence to use, they may source some of their produce from community groups which are collecting in the wild or have a small plantation, or perhaps they have some minority equity holding of indigenous people and indigenous staff.

"While all of those moves are positive, in Australia it still remains very rare to have any complete supply chain of traditional products that is 100pc indigenous owned and managed," Mr Barnett said.

"The good news is that the trajectory in terms of international conventions and Australian jurisprudence is such that indigenous rights to participate in the economy will increase.

"There is also a very clear sign that intellectual property law will increasingly reaffirm intellectual property rights over traditional knowledge and genetic resources, so the sector is going to have to adjust to have a much greater level of indigenous ownership in it."

Almost every species in Australia has some form of traditional use 1000 years ago, but only some of those species have commercial value in mainstream markets.

They tend to be the species that can be used for cuisines, so they have a taste benefit to create unique flavours, species that are super-food type products, or species that can be used for traditional medicines.

However, that doesn't mean that there aren't products that haven't yet been discovered commercially that markets couldn't be created for.

Mr McGuire said there were less than 20 species that were currently commercialised in Australia, yet there are literally thousands of native species out there.

"The upside and potential is massive for Aboriginal people to not only participate, but open up in terms of the sacred knowledge when it comes to those species," he said.

"The opportunities with commercialising those products are massive - you've got 2000 species of acacia alone so that's massive industry just in wattle seed, particularly when some of those really commercially attractive species fetch between $150 and $250 per kilogram."

Overall, NLE is committed to developing the industry and participating at a national level, but doing so with their own perspective and context for what they want to do on their own country.

"Cultural authority is very place based," Mr McGuire said.

"No one has a right to interfere with other groups and their knowledge when it comes to using produce and the opportunity for products to be developed within their own country.

"Embedding that into legal speak and legal constructs is the massive challenge that we, both as Aboriginal people and as a nation, face."

Mr Barnett said when it came to the issue of indigenous ownership of intellectual property associated with sacred knowledge, legislation would definitely be really helpful, but there was a possibility that the market would figure it out for itself.

"What we're seeing is increasing demand, particularly from restaurants and food companies that have reconciliation action plans, that businesses demonstrate they are acquiring traditional produce from a genuine indigenous supply chain," he said.

"They want those businesses to have verification that the products were harvested and processed with traditional methods by the right people with the cultural authority to do so.

"Legislation is helpful in the sense that it creates the rights and makes them legally enforceable, but it also raises the profile of the issue which makes people more aware.

"However, the most important piece to this whole puzzle is supporting Aboriginal businesses in this space so that they can grow and be competitive in the marketplace."