AUSTRALIA has had a remarkable half-decade.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

We had one of the worst east coast droughts in living memory, followed by a fantastic run of wet weather.

Our cropping has achieved record volumes and looks likely to continue with a well above-average season yet again.

In fact wet weather is likely to be the biggest risk nationally, not the risk of lack.

This is a two-edged sword.

While prices have been very high of late, at a flat price level, wheat prices have been as strong as they were at the height of the drought.

The 'flat price' is the price given to farmers and includes basis, currency and futures.

So we can be forgiven for thinking that prices are good.

We have to look further into our pricing levels.

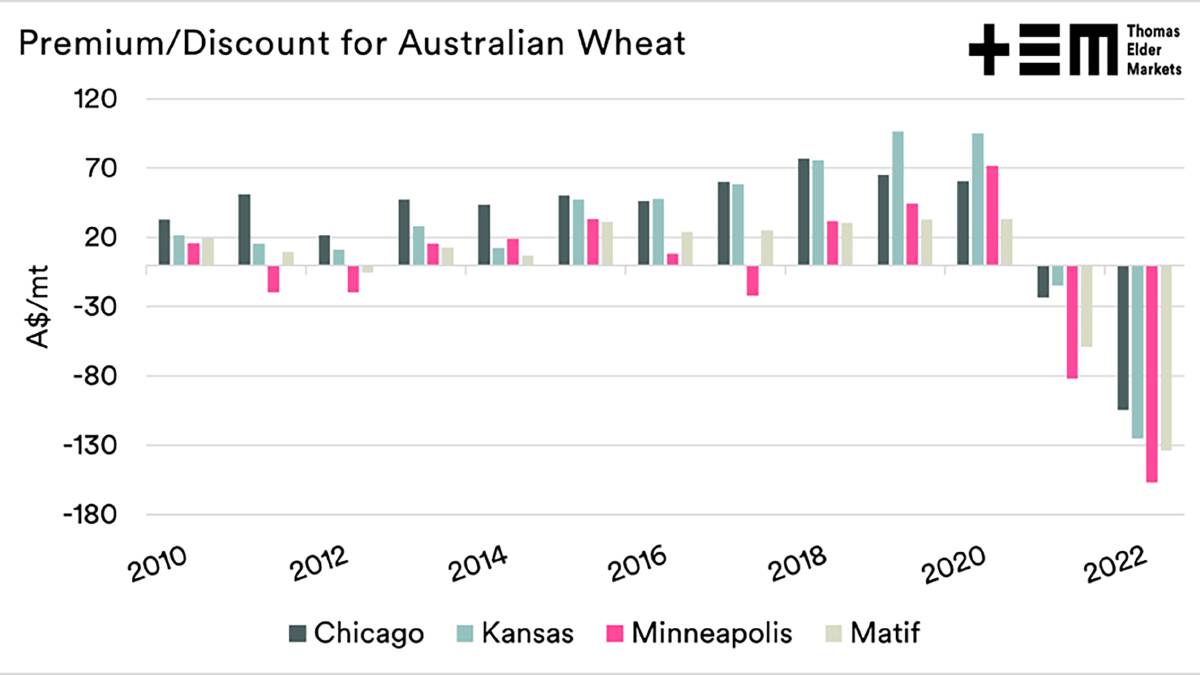

Chart 1 shows the annual average basis level between our local pricing and a range of overseas futures contracts.

Our basis level has typically traded at a premium, but the past two years have seen us sink to a major discount.

The term basis is exchangeable with difference.

When someone is talking about basis, they are discussing the difference between two different prices, generally between physical and futures.

In general, in Australia, basis is often a comparison of Chicago Board of Trade (CBoT) soft red winter wheat (in Australian dollars per tonne) to our cash prices.

Although whether CBoT is the relevant indicator is a discussion for another day.

The basis level can be either positive (premium) or negative (discount) to CBoT futures.

Australian basis levels tend to be positive, with very minimal time at neutral or negative levels.

The largest driver of basis levels is the local supply of grain.

During the drought, basis rose to extreme levels.

The premium was due to the drought-induced deficit of grain on the east coast.

When supply is low, the basis level tends to rise rapidly, providing producers with a very strong premium over international values.

The converse occurs when Australia has a good year.

When the local supply of grain is at a large surplus, the basis level declines, as the domestic market does not have to pay up to cover requirements.

The larger the production, the more pressure that will be placed on basis levels, and our premium versus the rest of the world will decline.

Over time a lower basis level tends to mean that production was strong.

In contrast, high basis levels generally mean that the majority of farmers don't have much to sell to capitalise on higher levels.

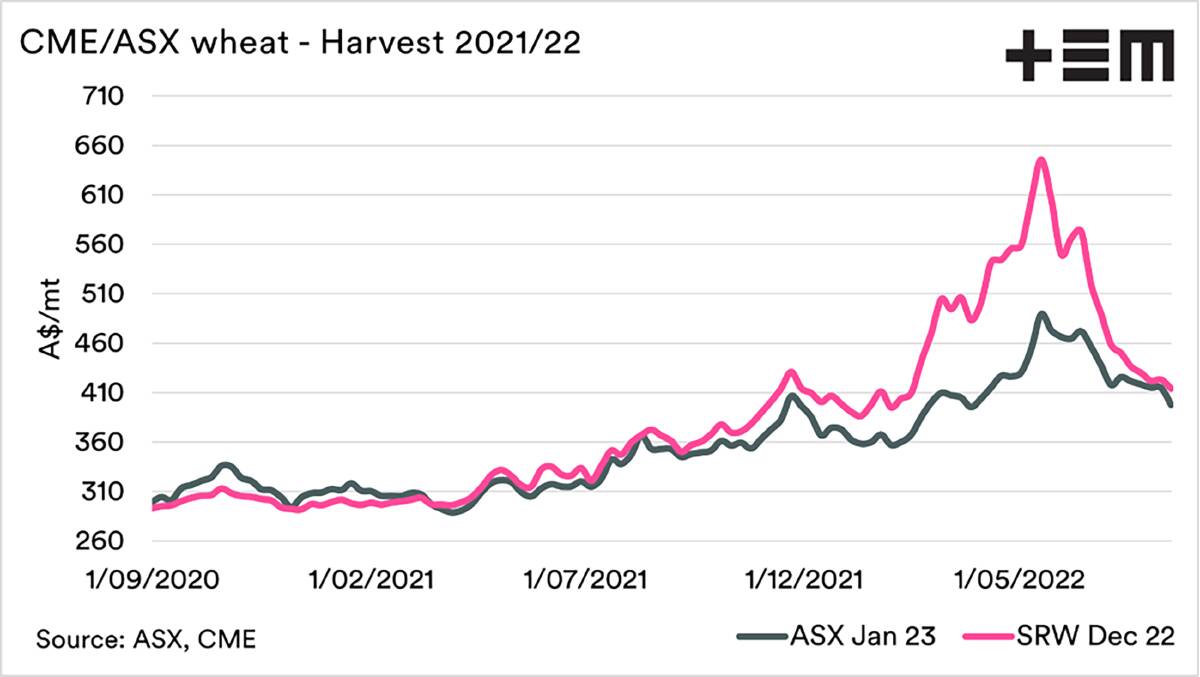

Chart 2 shows the ASX and CBoT wheat futures price for the current harvest.

The ASX value gives a decent representation of east coast values.

We can see that the premium for CBoT has narrowed in recent times, however as we move closer to harvest there is a risk of discount growing if our crop grows larger.

As we have bigger crops and the logistical challenge becomes, well more challenging, then we may find that our basis stays at discounted or parity for longer.

As someone asked me recently - "when will we get large premiums again", well most likely in a drought.

READ MORE: