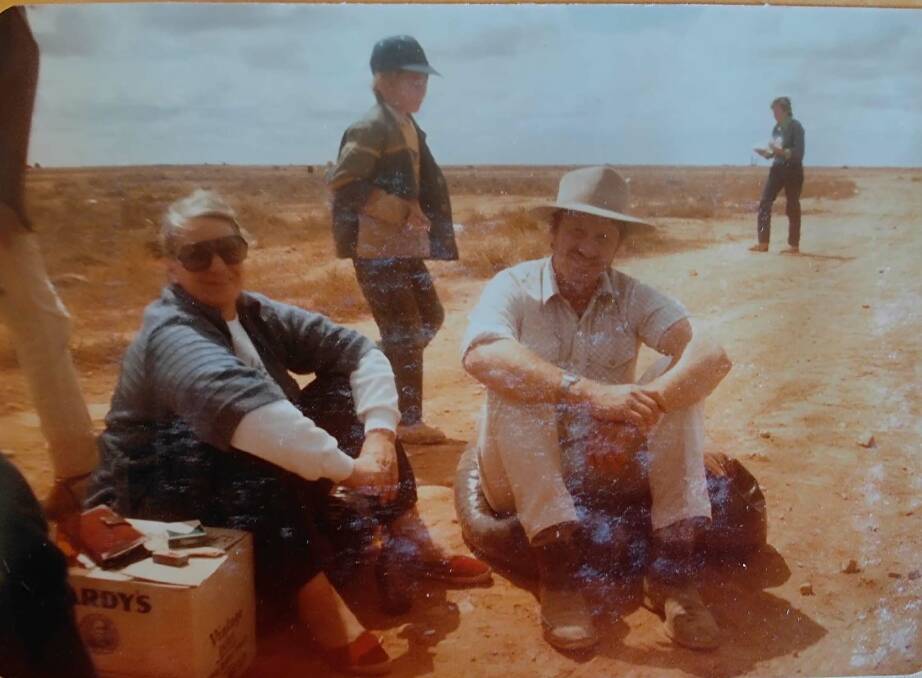

A love for the red outback dirt - in particular that of Rawlinna station - has passed through three generations of the McQuie family.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

Grandfather Murray, father Dougal and granddaughter/daughter Matilda each represent a different time and era, however, their stories are similar in many ways - a demonstration of unwavering perseverance and resilience.

Farm Weekly spoke with Murray and Matilda about life working on the land of Australia's largest operating sheep station - situated 400 kilometres east of Kalgoorlie - in both the 1980s to 1990s, and now.

Photos courtesy of the McQuie family and Jill Campbell.

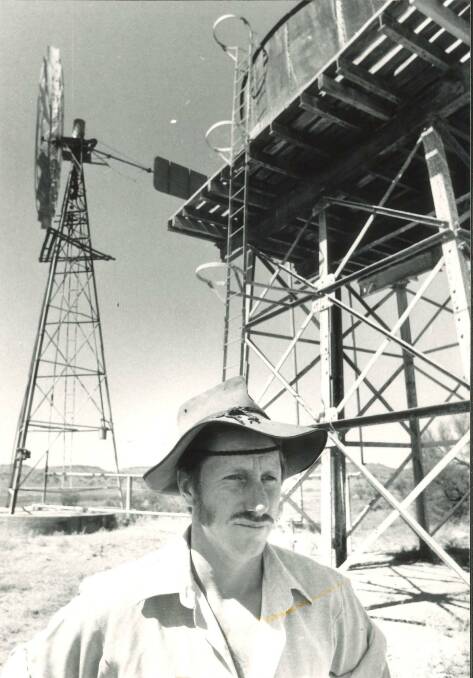

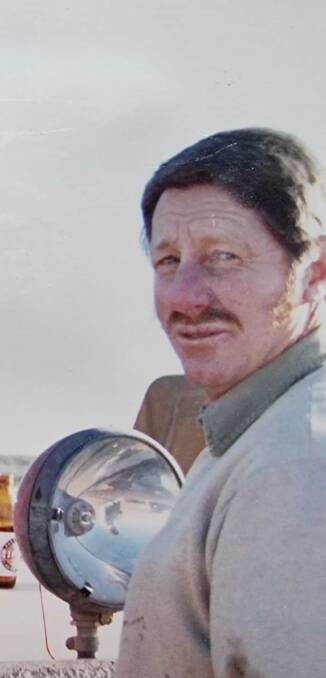

MURRAY McQuie's heart beats through the vast and sparsely populated stretches of the Nullarbor Plain.

Despite living in Kalgoorlie for some time now, he'll always call the bush home.

Serving as Rawlinna station's manager from 1982 to the late 1990s, Mr McQuie's zest for life and ethos of hardwork earned him a reputation for being 'a bit of a legend'.

In fact, it was in that time, wool bale was king and so too was the now 84-year-old, after overseeing one of Rawlinna's biggest ever shearing seasons.

Before Mr McQuie retired, a team of 16 shearers worked through close to 80,000 sheep - including two ram shearings - to produce a 1800 bale wool clip.

Decades may have passed since, but Mr McQuie remembers the season as if it were yesterday.

"The woolshed was running at full steam," Mr McQuie said.

"Unfortunately for me, I think our numbers were bettered by 200 bales the following year, when Ross Wood was manager."

Spread across more than a million hectares - and covering an area roughly the size of Sydney - outback royalty Rawlinna has long reigned as Australia's largest operating sheep station.

It was developed by Jumbuck Pastoral from infancy, after previous managing director Hugh G MacLachlan first placed a survey peg in the ground in the 1960s.

History is not lost on Mr McQuie and working at Rawlinna has become somewhat of a family tradition, carried on by son Dougal and now granddaughter Matilda.

Mr McQuie weathered brutal bushfires and drought, a cyclone, wild dogs and the wool market crash in his 16-year stint to keep the station going.

They build 'em tough out bush, and he proved tougher than the tough times.

A love for the land

Surprisingly, Mr McQuie did not fall in love with the station way of life on the Nullarbor Plain.

"I was born in Melbourne, but my mother's family had country in Wentworth, New South Wales," he said.

"In the war years, I would catch the train to Mildura with my parents during the school holidays to visit my grandfather's sheep property (Bulpunga station) at the Darling River Anabranch.

"I think that's where it all started."

Back in those days you needed to either personally fund university or be offered a Commonwealth scholarship.

Mr McQuie missed out, but was still able to steer life in a direction he wanted - starting at the station he visited as a child, Bulpunga.

After nine months, the then 18-year-old landed a role jackarooing with South Australian-based Mutooroo Pastoral Company, known as a jackarooing school trainee ground.

A fast learner, Mr McQuie moved through the ranks and went on to manage all three of Mutooroo's properties in succession over 16 years.

At this time he also met his wife Marg.

Eventually, Mr McQuie decided it was time for a change and accepted work with BH MacLachlan at Granite Downs cattle station, in northern South Australia.

The year was 1972 and the MacLachlan family had built one of Australia's largest pastoral empires with stations dotted across the country.

Originally, Granite Downs was purchased with the intention of running sheep.

However, the boundary fence was never completed because the neighbouring properties couldn't afford their half of the netting, after years of drought.

When Mr McQuie arrived there were about 2000 Shorthorn cattle, along with infrastructure, water points and country that desperately needed to be developed.

He drilled bores, dug dams and laid miles of poly pipe.

Little did Mr McQuie know, the time spent at Granite Downs would become the best years of his family's life.

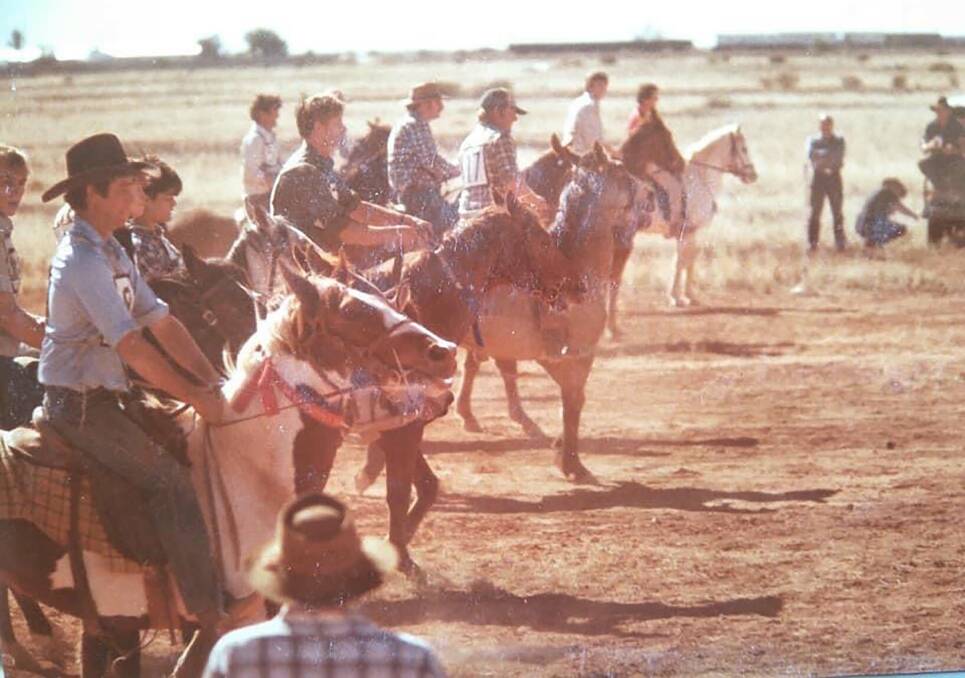

"Granite Downs was run as an open stock camp with about 10 Aboriginal stockmen," Mr McQuie said.

"There were no yards or handling yards - it was all horse work.

"We had 40-odd horses in the camp, which were hobbled out to feed at night by the horse tailer and used for muster, as well as specialist bronco horses for branding cattle.

"We carried the sale cattle along with us and the kids (sons James, David and later Dougal) spent a lot of time tailing bullocks at the same time."

In the late 1970s, Mr McQuie augmented the original horseback mustering with aerial spotting.

The timing could not have been better, as he was able to pull in some big-framed bullocks and cattle just as the market turned and go on to finish a 'fantastic season'.

Not long after, the brucellosis and tuberculosis eradication campaign started in Australia, which meant work was done to internal fencing and yard building and the open stock camp was no longer.

When Mr McQuie left Granite Downs, cattle numbers were at 10,000 head and large spaces of the country had been opened up.

"We spent 10 years there - it was the best time of our lives," he said.

"We found a lot of personal and working freedom in running cattle.

"However, the property was listed to be returned to the Aboriginal people along with the north west reserve.

"So it became a closing situation and at the same time I received a letter from Hugh MacLachlan (BH MacLachlan's son) asking me to take on the role at Rawlinna."

Rawlinna's roots

In the late 1950s, BH MacLachlan's eye for good sheep country wandered across the flying red desert in Australia's heartland.

Mr MacLachlan was travelling from Adelaide to Perth on the Trans Australia Railway and, unlike most, saw the Nullarbor Plain as land of opportunity.

His son Hugh's line of thinking was much the same and the area was surveyed in 1962.

Hugh placed a peg in the ground and applied for a pastoral lease thus Rawlinna - the Aboriginal word for wind - came into being.

By the time Mr McQuie arrived some 20 years later, the station had been significantly developed by Mr MacLachlan, its first developing manager Roderick Campbell, Clyde Bant and Mr McQuie's previous manager David Seaton.

Areas had been reduced to more manageable sizes and a fence on the nightshade block - where wethers were run - had been electrified.

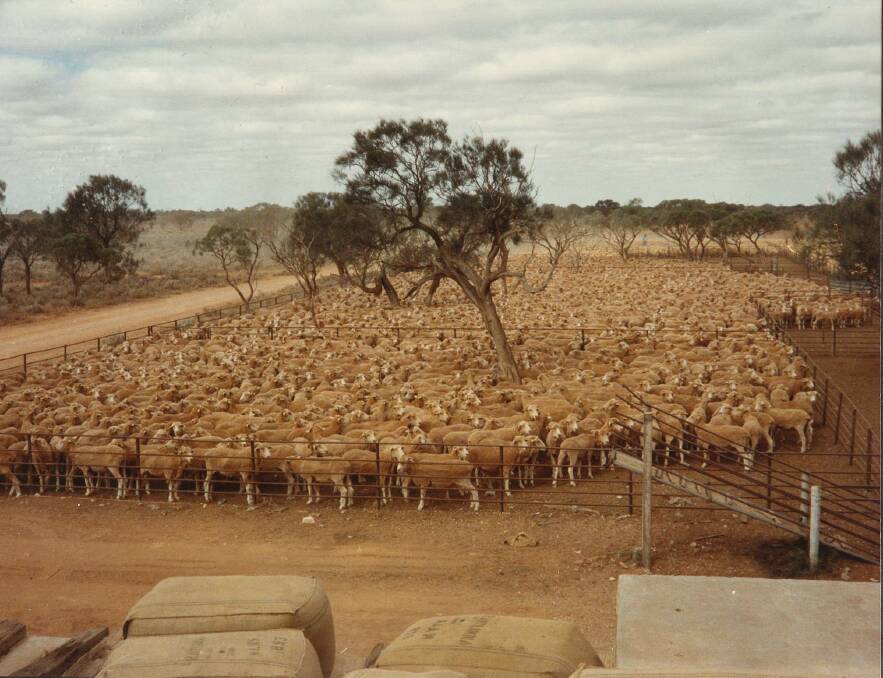

Rawlinna's sheer size had to be seen to be believed, with 50,000 Merino sheep spread across more than one million hectares.

Granite Downs had ignited Mr McQuie's love for horse and cattle work, so he wasn't keen on returning to sheep.

Ironic, given he was overseeing the largest operating sheep station in Australia.

In Mr McQuie's first lambing season at Rawlinna 20,000 lambs dropped from 22,000 ewes.

He said more common than not, six-year-old ewes would lamb at 100pc.

This was owed to the open country, which allowed sheep to run in 'good mobs' and frequently mix with each other at watering points, as well as the complete eradication of wild dogs.

Numbers were so high in fact, that cast for age and older ewes were sent to market.

"From memory, we put a lot of sheep into the Bruce Rock and Merredin market in my first year," Mr McQuie said.

"We showed our place on the map, I think we sold about 10,000 wethers at Merredin.

"Our numbers were right down, but we'd regularly run anywhere up to 60,000 head."

Fortunately, Mr McQuie was no stranger to shearing in large numbers.

Having worked at Mutooroo Pastoral Company's Mulyungarie station in the past, it was normal to shear 40,000 head in a season.

What Mr McQuie did find challenging was how significantly the sheep industry had changed in the decade he was working with cattle at Granite Downs.

By the 1980s, the wide-toothed comb had been introduced and the speed shearers were working at was much faster than Mr McQuie remembered.

The wool room was also largely staffed by women.

"On my first day of shearing I thought, 'How the hell am I going to keep up with this?'," he said.

"I decided to put the old ewes in to be shorn ready for market.

"Well these blokes went mad - I planned for about 150 sheep per man and they ended up shearing more than 3000 to 3500 head between them.

"My plans were completely thrown out the window."

The next day, Mr McQuie put old aged wethers through the shed to slow the team down and revised the shearing plan.

Staff were flat-out moving woolies to keep up with the shearers.

"Off-shears sale sheep were walked north to Rawlinna siding and railed west to market," Mr McQuie said.

"The following year, after big lambing numbers, my focus turned to culling the weaners at shearing time to improve wool cuts.

READ MORE:

"Fluffy and fine woolled, low cutting types were culled, along with excessively strong wool types, leaving a medium micron, heavy-cutting line of one-year-old maiden ewes for mating."

It took a few years, but eventually Mr McQuie was able to present a 'pretty good' line-up of sheep with an average three-inch staple and 22 micron.

In fact, the clip was so even the wool classer said they would 'almost be put out of a job'.

At shearing time, days and nights often carried on through together - off the back of a work hard, play hard mentality.

"My team put in some terrific hours and did a fantastic job," Mr McQuie said.

"There was only enough room to hold 20,000 sheep around the woolshed and in shearing paddocks.

"When we were shearing 60,000 head, numbers would change over three times to get the sheep through.

"On any given day, there could be anywhere from 10,000 or more head on the move, coming and going."

Rawlinna owed its ability to run such large numbers to Mr MacLachlan and a wild dog proof fence.

Click go the shears

When you run a large number of sheep, you need a shearing shed to match.

For Rawlinna, this was a 16-stand, two-storey shed at the Depot, which ran at full capacity for about five weeks.

The station comprised four leases, the first shed was at the homestead, where the railway line development started in 1962.

After six years, shearing was moved into the Depot shed - where it is run now.

Similarly to more recent times, shearing was held in February to March and the surplus was turned off in autumn to reset stocking for the following year.

The surplus was sold every year and the stocking rate was set at shearing time as to what the station could hold and what would be sold.

Older ewes, ewes and young-classed sheep were turned off every year this was to maintain the ewe or breeding flock.

Peak of the drought, Mr McQuie shore older ewes in the early summer and weaned their lambs, before they were sold to reduce numbers.

"There were two eight-stand boards, one either side of the shed and the wool came together at one end," he said.

"The wool would come up the two boards and aggregate in the wool room where a classer operated."

Joining was in December and the rams were taken out at shearing time for convenience.

Mr McQuie recalled often selling six-year-old ewes in lamb for five dollars per head, before stock reduction time.

"I often couldn't get markets for them, this was prior to stock reduction when we were forced to shoot to reduce numbers," he said.

"Nowadays, those ewes would be worth well over $100."

Large numbers of wethers were run in the saltier country until the third year, when they were sold for their wool cut.

At Rawlinna's peak, Mr McQuie recalled sheep numbers tipping the high 70,000-head and in the tougher times the lowest number was 39,000-head.

The reduction in numbers was about the time the wool market collapsed in the late 1980s and was the last year Rawlinna sent a wool cut as a complete clip.

In the years that followed, it was instead sold in individual truckloads and spread over the market.

"When railways stopped running intermediate trains we started taking sale sheep to the station's south," Mr McQuie said.

"We had a loading yard built right on the Eyre Highway, so we would walk the sheep there, to go straight on bitumen."

Sheer hard yakka

"Do you reckon you blokes could drive 10,000 sheep for 60 or 70 miles?"

That was the question Mr McQuie put to his team at the end of the first shearing season, wanting to move the large mob of weaner ewes to the north east section of Rawlinna.

Not afraid of hard work, they accepted the challenge and got it done in one go using horses and motorbikes.

Droving wasn't the most difficult part, it was actually watering a flock of that size, once it had reached watering points.

So temporary yards were used to hold the sheep at night.

"It took hours to get them through the trough, but we did it," Mr McQuie said.

"I venture to say, it was probably the biggest number of sheep droved in those days.

"It was quite an effort and a great lesson for everyone involved when it came to stockmanship."

Laneways weren't used at that time, so Mr McQuie instead elected for mobs to be taken into a different direction almost every drove.

He didn't want to damage the country, particularly running mobs of up to 10,000 sheep - including 5000 ewes and their lambs.

"They would create a hell of a lot of dust, which filled their wool,'' he said.

"This would cause big problems when - and if - it were dry, because we had to make sure the clip didn't dust up on the way into shearing."

Sheep were run in ages of birth, with one-year-olds drops isolated at a separate part of the property.

During muster, stockmen would work hard to group sheep together and walk them into depot holding paddocks until they were wanted for shearing.

The same went in reverse, after sheep were shorn they were moved back into holding paddocks, mustered out and walked away.

The job eventually became easier when Mr MacLachlan approved aerial mustering on the station - which was a game-changer.

Mr McQuie controlled everything from the air, while a crew remained on the ground.

"From about 60-odd-thousand sheep we would only have a few hundred stragglers," he said.

"We produced very clean musters and concentrated on every sheep and ram coming back.

"The rams were separated from the ewes at shearing - this meant we had a very concentrated lambing.

"The whole situation was very well controlled."

When it rains, it pours

Twelve years into Mr McQuie's role, Rawlinna was struck by a big season.

A cyclone hit and heavy rain further north near Leonora filled Lake Boonderoo - at neighbouring Kanandah station - for the second time in white man's memory.

It was first filled in 1974.

Lakes Braeside and Rebecca also filled and overflowed down Ponton Creek to fill Boonderoo, expanding out to an area of between 50 to 80 square kilometres.

The cyclone caused significant damage across the Goldfields and even cut the Trans Australian Railway and Eyre Highway on the Nullarbor for many days.

High growth combined with rainfall, wind and lightning strikes created the perfect storm and 'one of the worst seasons' for bushfires at that time.

Speargrass was standing up to three feet and seed had dropped to its base.

"The seed burns pretty prolifically once it gets going," Mr McQuie said.

"It's like lighting methylated spirits - you don't see the flame in it, it just runs through it.

"We were fighting fires from October through to Christmas time."

Mr McQuie served on the frontline as chief fire control officer and was joined by a co-ordinator from Northam's rural fire brigade, who had access to a telecommunications trailer.

Nullarbor pastoralists were under immense pressure and graders were used to flank and turn the bushfire back on itself.

The fires ripped through the plain for some time and conditions at night proved better to operate in.

Fortunately, Rawlinna did not lose any sheep in the fires.

"We were able to keep in front of it and double back through the burnt ground, so there weren't any big stock losses in it," Mr McQuie said.

"They were still difficult times.

"I remember being so exhausted, I was travelling around various camps when we finally put out the fire.

"Driving back to our swags, the flat Nullarbor didn't look so flat anymore and it was a real battle going back to camp."

Beyond the bushfires, the three foot tall speargrass also caused headaches in sheep fleece.

In a normal season, speargrass only grew about three inches and the sheep loved it.

However, when it reached the stage of burning - usually off the back of a cyclone or less commonly a prolific season - Mr McQuie said there was a real problem.

"You can't walk sheep through it, their fleece gets full of seed," he said.

"Some years we would send livestock to market and get penalised because the seed would come right through the skin and stick to the meat.

"When they are skinned off you have all these speargrass seeds sticking through the skin."

Another challenge that came with the water was the kangaroos.

Fences had been built to keep wild dogs out, but ultimately kept the kangaroos in to breed uncontrollably.

Shooters helped reduce numbers by 10,000 per year.

Mr McQuie estimated that was only a quarter of how many were actually at Rawlinna.

This meant the station was not only watering and feeding 60,000 sheep, but two-thirds of that number in kangaroos.

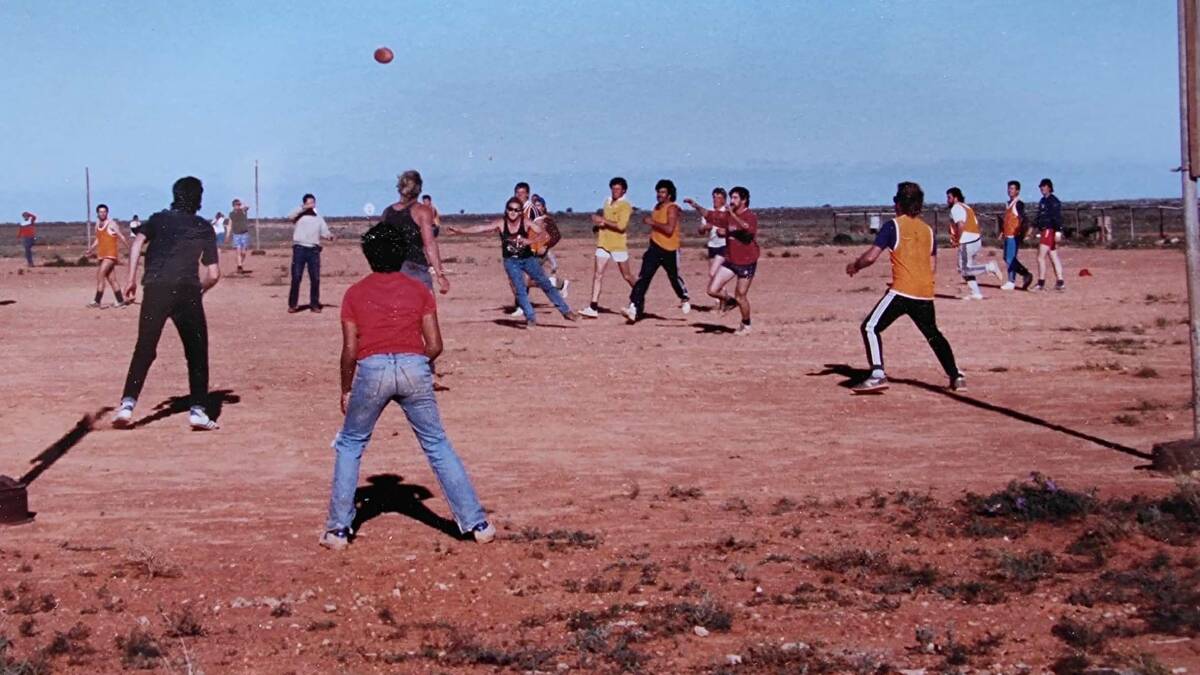

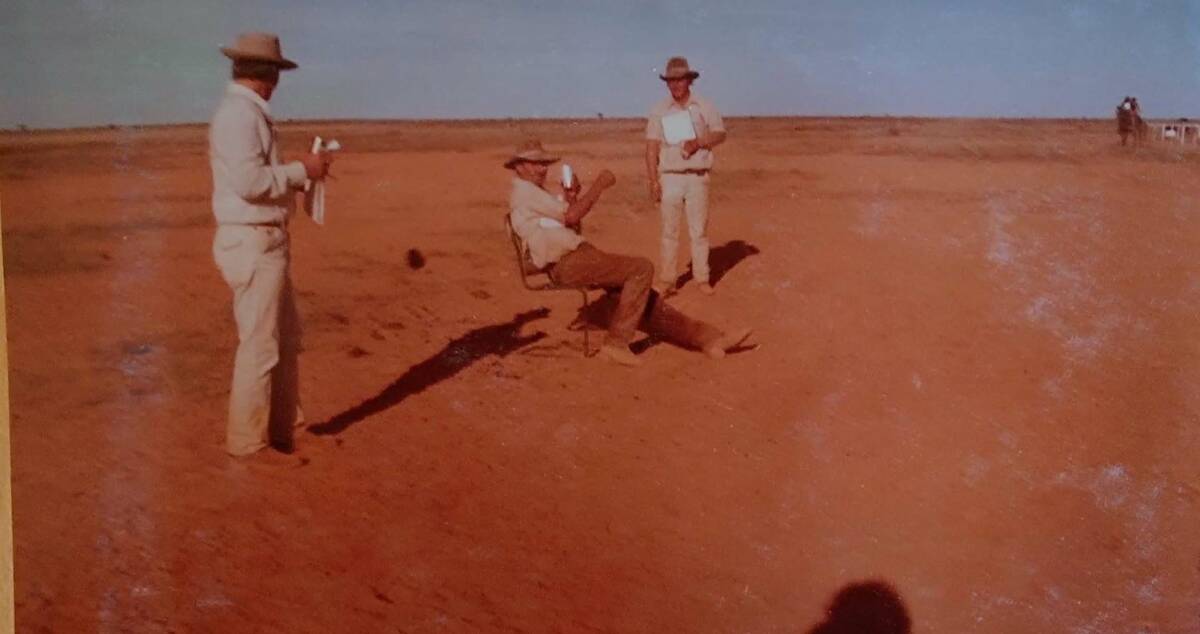

Community, cricket and behind-chiller consults

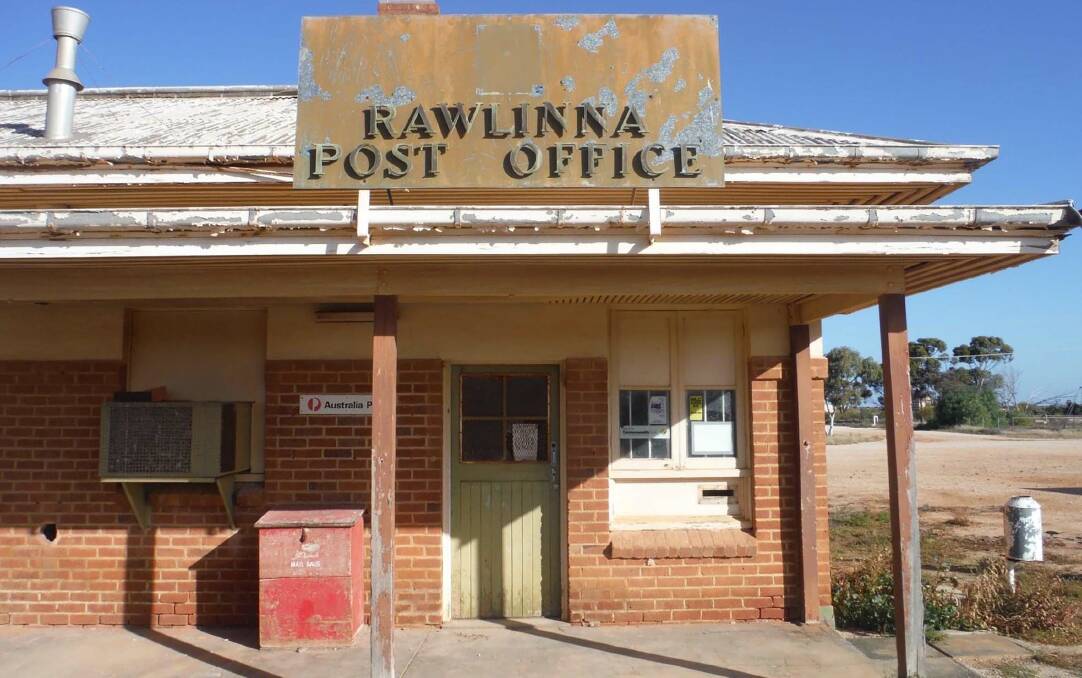

Once a tight-knit and thriving settlement, many people left Rawlinna siding, after the trains stopped pulling in.

A school, post office, bank, nursing post and several homes - occupied by workers, families and kangaroo shooters - dotted the area hidden off a dusty sealed road.

When you live somewhere as remote as the Nullarbor, it is important to keep spirits high and bring people together.

Mr McQuie said a friendly game of bush cricket was a popular way of doing so.

Making do with what they had, residents made a winning cup by using the screw on top of a gas bottle, a couple of dog-spiked clips, which were used to hold the railway line to sleepers and a fish plate.

For Mr McQuie there was much more to the game than winning and bragging rights.

What he was most pleased about was the fact the game was played in January, right before shearing started.

"I had a lot of new staff getting ready for the shearing season," he said.

"They were all just individuals, so we weren't a crew at all.

"I took them interstate to Cook, South Australia, to play cricket and we welded into a pretty good team."

Outside of sport, Mrs McQuie (Mrs Mac) was quick to build a well-respected reputation at Rawlinna township as the pre-primary school aid and the clinic nurse.

She combined the two roles - working at the school in the morning and the clinic in the afternoon - right up until the township closed down.

Despite her kind and approachable nature, the town's men would rarely go to the clinic, as it was considered "women and children's" business.

"One Friday arvo, someone came off the line and the first thing they did was grab a beer from the store," Mr McQuie recalled.

"There was another room alongside the store with a chiller and storage room.

"Mrs Mac was grabbing something before heading home and was idled up by a bloke, who asked if he could have a word."

"Not here," the man said, and ushered Mrs Mac behind the chiller for a consult.

Word spread and soon it became a regular way for men to discuss an ailment.

They couldn't be seen going into the clinic, because then they'd be admitting something was wrong with them.

"Mrs Mac, can I see you behind the chiller?" they would say.

The usual appreciation for a behind-chiller-appointment was a stubby of beer.

Bulga Downs and Bobby

1984 wasn't just remembered as a big season - it was also when the McQuies purchased Bulga Downs station, near Mount Magnet.

Having managed large pastoral companies for 20-odd years, the prospect of buying a sheep station for themselves was appealing.

Mr and Ms McQuie paid the necessary loans and stayed at Rawlinna, while their two eldest sons James and David went on to manage Bulga.

About 40 years later, the station is still being overseen by David, however it was converted from grazing sheep to Angus cattle during the 1990s due to wild dog problems.

Mr McQuie would communicate with his sons in the earlier days from Rawlinna, via Royal Flying Doctors Service shortwave radio.

"We were fortunate the reception between Bulga and Rawlinna was generally good," he said.

"So good, in fact, that when the boys were in Sandstone or at one of the various race meetings around the area they would rig up the portable transceiver and give me a graphic description of the problems they found with the windmill column they were pulling."

Bulga was right in the centre of ex-Tropical Cyclone Bobby as it tracked south.

Rain turned torrential, after it was sucked in and turned around inside the cyclone.

Bulga had two years of rain in two days.

The Sandstone road across Lake Noondie was under metres of water and remained impassable for 11 months.

"David had shut off a yard to trap a ration sheep (for meat) prior to the rain," Mr McQuie said.

"He managed to get there on a motorbike and bring a wether home.

"He and Vicki lived on mutton and mushrooms, which was all they had for a few weeks - the mushrooms came up in the sheep yards at the shearing shed.

"David eventually swam a little 4x4 Suzuki to Kalgoorlie for stores, bringing back essentials for Perrinvale and Cashmere people as well."

The water from this area cut the Leonora-Kalgoorlie Road and eventually ran from Lake Raeside via the Ponton creek, cut the east to west railway line to end up in Lake Boonderoo.

When Mr McQuie was finally able to reach Bulga from Rawlinna, he was devastated to find virtually everything had washed away.

"I expected green grass aplenty, but there was nothing," he said.

"Seed gone, fences gone and even sheep gone."

End of an era

After 16 years at Rawlinna, Mr McQuie decided it was time to hang up his boots.

It was difficult to secure a workforce and serious manpower was needed to manage flies, crutch and mark lambs.

He and Mrs Mac moved to Bulga and intended to help David make the station payable or saleable.

With them they took a road train loaded with 600 to 800 older ewes in lamb to help boost sheep numbers.

While there was a great percentage of lambs, Mr McQuie saw few grow out.

Around the same time, the wild dogs arrived.

The McQuies spent two to three years fighting them, but - like many pastoralists - they weren't winning.

"Come shearing in January to February we were down to just 300 ewes," Mr McQuie said.

"The dogs were beyond us and eventually put us out of sheep entirely."

The McQuies received a grant through the Gascoyne-Murchison strategy to fence an area for cattle.

When David and his wife Vicki married, they received a gift of 40 heifers and one bull from Vicki's father at Tieyon station, in far north South Australia.

Those cattle were bred up and started over-running the sheep infrastructure.

They became the nucleus of the cattle herd.

Cashmere Downs was then advertised for sale and David put forward a proposal to acquire the working area of the station in exchange for the undeveloped area of Cashmere and the McQuie's portion of Ida Valley.

"This eventually happened after a false start or two," Mr McQuie said.

"In 2001 we shore 6000 sheep from Bulga and Cashmere.

"We did this for three years, but by then we were down to 600 sheep due to wild dog predation."

In 2013, Dandaraga was added to Bulga Downs, to give the family a sufficient area for a stand-alone cattle business.

A system was developed to keep the wild dogs at bay, and Mr McQuie said he was happy with the balance at the station.

He was also "happy enough" to be running cattle again and continued doing the station's water runs and checks.

"When I came down to the Nullarbor from Granite Downs I really didn't want to go back to sheep,'' he said.

"I enjoyed the horse and cattle work."

Almost two years ago, the McQuies moved from Bulga to Kalgoorlie, as Mrs Mac was unwell.

Today, Mr McQuie ventures out to the station "every now and then".

What he misses most about life out bush is the infinity land.

"You get to know it really well, you make your judgments on what you see, the state of the country, wild dogs and rainfall," he said.

"It is all a picture you gain by driving around and observing."

Rarely seeing cattle - as they are spread across thousands of hectares -Mr McQuie gained knowledge from the tracks they were running.

"When it is dry you see them around the waters,'' he said.

"You know what they are like or if they are going downhill, it is getting dry and they are calving.

"Some of the time you are deducing all of that by observation.

"I miss that - the water run, getting around the station and keeping up to date with how the seasons are."