"THE trade is dying'' is one of the main arguments used against live sheep exports by sea.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

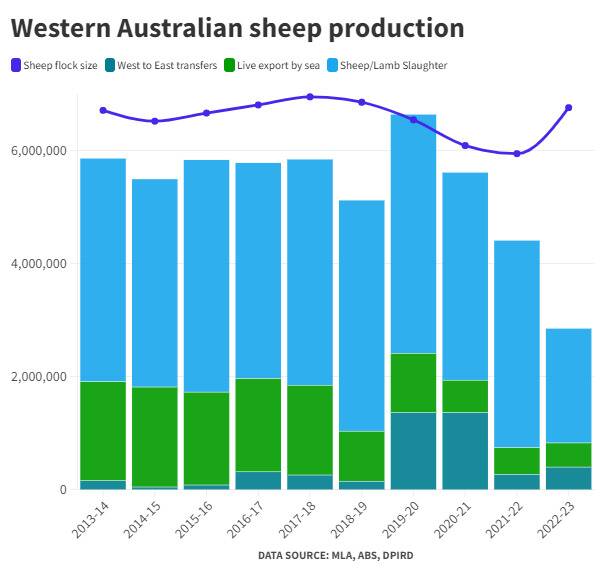

At first glance this may be mistaken as truth, with about 500,000 head exported last year - after peaking at 7.6 million head in 1987.

But numbers alone don't tell the entire story or highlight the reasons for the slide.

In the past decade, multiple factors have affected the live sheep export industry at different times.

The decline started in 2012, after the Exporter Supply Chain Assurance System (ESCAS) was introduced to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and Saudi Arabia ended shipments from Australia.

Read also:

To paint a picture, 1.9m sheep were exported by sea in 2013, compared to 2.4m in 2011.

Implementation of the Northern Hemisphere moratorium followed in 2019, which prohibited trade to the Middle East from June to September.

A year later, 1.3m sheep exited Western Australia, as the Eastern States emerged from severe drought and farmers started restocking.

This saw live exports fall from 1.04m head in 2019-20 to 571,223 head in 2020-21.

According to Episode 3 director and agricultural market analyst Matt Dalgleish, the mass exodus masked the importance of having market alternatives.

Mr Dalgleish said there was no competition in price, demand or supply - something to which live export would normally contribute.

Now, WA producers have thousands of extra sheep on-farm, processors are working through a lengthy backlog and there is an oversupply of lambs.

Unlike two years ago, Victoria, New South Wales, and - to a lesser extent - South Australia, aren't coming out of drought and don't need the numbers.

"Without live export and no real numbers to note heading east, there is nowhere for WA ewes and lambs to go," Mr Dalgleish said.

"If held on-farm for too long, lambs end up being classified as hogget or mutton and there's potential for continued discounting.

"The moratorium has just started, meaning WA has potentially three months without options to serve animals.

"Farm Weekly spoke with Mr Dalgleish about changes in east to west movements, slaughter, markets and WA's flock - all of which have, over the years, played a part in live export trends.

East to west movements

More than 2m ewes and lambs were transported across the Nullarbor to the Eastern States in 2020 and 2021.

This was largely due to restocking activity, after a severe drought, and smashed WA's previous decade-long record of 1.07m head.

According to the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, more typical figures returned the following year, with 267,600 adult sheep (47pc) and lamb (53pc) interstate transfers.

In the financial year to date, numbers increased by 55pc compared to year-ago levels, with 395,600 adult sheep (28pc) and lambs (72pc).

"At the end of the drought in 2019, Eastern States' producers were actively looking for sheep and the west was able to provide them, where local supply could not," Mr Dalgleish said.

"However, that activity and enthusiasm to rebuild doesn't happen every year.

"The reason such big numbers were transferred in that time is there were three months of the year when live export wasn't operating (due to the Northern Hemisphere moratorium).

"Trans-shipment to the east picked up the slack.

"For part of 2020, the normal discount seen in pricing between west and east, wasn't as low as previous years.

This was compared to $30 per head in 2019 and $40 per head in 2018, which WA reverted back to in 2021 when numbers returned to a normal level by June-July.

Through the moratorium last year, Mr Dalgleish said the discount had gone beyond $50 per head.

"This signals a significant discount occurs during that June-September period when the eastern demand isn't there," he said.

"In the next few months, there is potential for that discount to widen even further.

"If it does, Eastern States producers may see WA transfers as a viable option.

"But it's not really a good outlet because producers are starting with a significant discount to what they could have been selling it, had a live exporter also been competing."

Slaughter

WA slaughter has been on the up with the Federal government's proposed phase-out of live sheep exports looming.

In 2020-21 and 2021-2022, turn-off reached about 3.6m head, compared to 4.2m in 2019-20.

To date, 2.03m ewes and lambs have been processed.

Mr Dalgleish said abattoirs had started to realise there was an opportunity to increase production and invest in plant capacity.

He estimated WA to be averaging about 80,000-head, or slightly less, of combined sheep and lamb slaughter per week.

This is up 35pc on year-ago levels, which nudged closer to 60,000-head.

"We have seen the increase at a time turn-off remains smaller due to ongoing restocking and remnants of COVID being problematic for the labour force," Mr Dalgeish said.

"I think meatworks are conscious that if live export is ended, they need to process enough when it is required - like when we revert to a flock liquidation phase.

"They are also well aware they have to offer good prices to keep WA farmers in the game."

Mr Dalgleish added: "The risk for them is if they can't, and they have to discount their pricing, there may be enough discouragement to send farmers out of sheep".

"They don't want people leaving the industry because it is not good for business," he said.

Flock

In the past two decades, there has been a changing dynamic to Australia's sheep flock composition.

Given the State is still dominated by Merino types (84pc breeding ewes), live export grew to become a more WA-specific sector.

WA's flock size sits at 12,750,000-head.

This is down on a 14,500,000-head peak during the past 10 years, in 2017-18.

In the Eastern States, where live export only accounted for 3-5pc of turnoff pre-moratorium, alternative versions aligned with the boxed market.

Mr Dalgleish said the trend was already well-entrenched with more east coast producers moving into prime lamb operations.

He labelled the moratorium as "the nail in the coffin".

"Merinos can handle the drier climate better, whereas prime lambs need better grass and rainfall outcomes,'' he said.

"You see the same in the west, but only really in the Great Southern area, which has favourable conditions.

"Other parts of the country that are heavily cropping can run Merino as well, but that's more of a side venture."

Mr Dalgleish said the big question was: "Do people switch out of sheep entirely because they may not have the ability to run prime operations there?

"Unless they start feedlotting, but that takes a lot of infrastructure in its own right."

Market

Australia lost access to its biggest sheep export market Saudi Arabia, after ESCAS was introduced.

According to a Meat & Livestock Australia outlook report, there has since been a concomitant (concurrent) decline in export market diversification from 12 MENA markets in 2002 to just five last year.

Lower cost competition, without ESCAS requirements or seasonal export restrictions, have taken a large share of MENA's live sheep export market.

In particular, increased supply has been provided by Romania, Spain, Portugal, Sudan and Somalia - among others.

In the subsequent years, Kuwait has taken the mantle as top trade destination for Australian live sheep.

Mr Dalgleish said Kuwaitis had heavily invested in feedlot and processing infrastructure and staff training, to ensure they would be able to satisfy imposed requirements.

He said trade value flowed to the Middle East for live sheep and boxed meat from all destinations.

This showed there had not been a trend away from live sheep exports and towards boxed products, with live sheep representing between 50-60pc of combined trade value of the two.

Last month, it was announced Saudi Arabia was on the brink of re-opening, after a revised health protocol was complete.

The protocol required lambs to be vaccinated for scabby mouth at marking or at least 30 days prior to export.

Return of the market could double current sheep export numbers out of WA by 500,000 head.

You have to ask, is this the sign of a "dying" trade?