There's no right answer, only the answer that's right for you

When Australians have their say in the Voice referendum on Saturday, October 14, there is no one right answer to the question they are being asked.

As University of South Australia Associate Professor of Law Joe McIntyre notes in his 7 rules for a respectful and worthwhile Voice referendum, you are not a woke idealist because you vote "yes" and you are not ignorant or racist because you vote "no".

There are valid arguments and concerns on both sides. There are uncertainties and different potential consequences with either choice.

Ultimately, every Australian voter has the right to make their own choice.

But every voter also has a responsibility to make an informed choice.

They owe it to themselves and they owe it to this country they call home.

As a democracy, we cherish the freedom to express a wide range of different perspectives and opinions.

Writing in The Conversation, Associate Professor McIntyre describes a proposal to change our constitution as an opportunity for us to listen to different views and to choose the type of nation we want Australia to be.

As University of Melbourne Associate Professor of Law William Partlett puts it, when we vote at a referendum "what we're doing is voting on an idea".

The 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart set out an idea from a significant group of Indigenous leaders for constitutional recognition of our First Nations people through the establishment of a Voice to Parliament. They invited Australia to walk a particular path.

Associate Professor McIntyre says we are being asked at the referendum "whether that path is, at this time, the specific path the Australian people wish to walk".

Given the lack of bipartisan support for the proposal and the complex social issues and history it seeks to address, many of our readers say they feel confused and overwhelmed.

This explainer, produced by the ACM network which publishes this masthead, examines some of the basic ideas and issues.

It focuses on the main questions that our readers have asked in extensive ACM Voice referendum surveys completed by thousands of regional Australians in 2023.

As this masthead has done in its news and comment sections throughout the debate, we have strived here to present accurate and impartial information. We have drawn from the official arguments for "yes" and "no" as well as the insights of experts.

At the very least, we hope this explainer helps you feel more informed on referendum day.

What is the Voice to Parliament?

A group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, elected by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, to consider new laws that would affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The Voice would provide this advice to Parliament and the executive government. The Parliament would not have to always agree with the Voice or act on the Voice's advice, but the Voice will be able to make recommendations for consideration.

Where did this idea come from?

Convened by the bipartisan-appointed Referendum Council, a constitutional convention of more than 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders met at the foot of Uluru in Central Australia in 2017 to consider options to formally recognise Australia's First Nations people. Of these leaders, 243 called for the establishment of a 'First Nations Voice' in the Australian constitution. Their 439-word "Uluru Statement from the Heart" called for Voice, Treaty and Truth.

Uluru Statement From The Heart

"We, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the southern sky, make this statement from the heart:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from 'time immemorial', and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or 'mother nature', and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia's nationhood.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are aliened from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future.

These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination.

We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.

How will the referendum work?

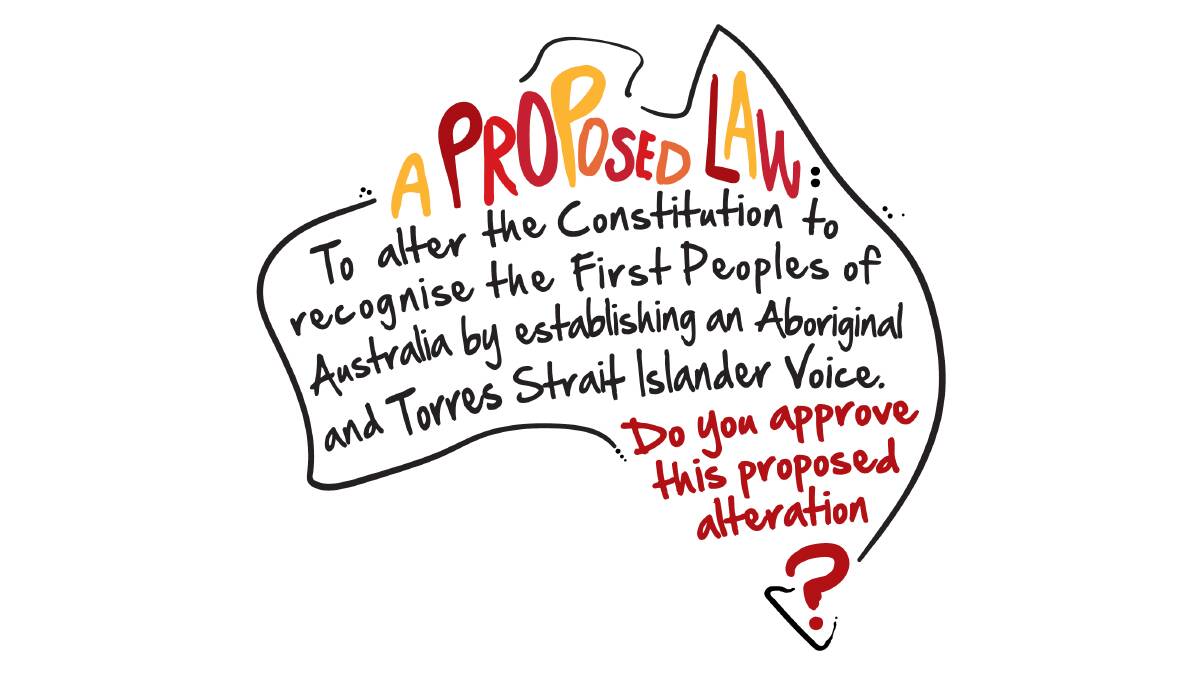

October 14 will be the 45th referendum in the nation's history and the first in 23 years. Like a regular election, it's compulsory to vote. All Australians on the electoral roll will be asked to vote on the following question:

A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?

You will be asked to write "yes" or "no" on the ballot paper. A national majority of Australian voters, as well as a majority of states (but not territories) need to vote "yes" for the referendum to succeed. If voters say "yes", the following words will be inserted into the constitution:

"In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures."

What is the constitution?

It took effect on January 1, 1901, and sets out the basic rules of government, establishes the composition of the Australian Parliament, describes how Parliament works and what powers it has. It also outlines how the federal and state parliaments share power, and the roles of the executive government and the High Court of Australia. Since Federation in 1901, Australians have voted in 44 referendums but the constitution has been changed only eight times. It can only be changed by a referendum - a vote of everyone in Australia.

Why does the Voice need to be in the constitution?

Governments have created and later abolished different bodies to represent the interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. Because these bodies were legislated, Parliament could legislate them into and out of existence.

If Australians endorse establishing a Voice in the constitution, Parliament will debate the details and decide the form and function of the body through regular law-making processes. They will need to ensure it works as intended, and that it reflects the expectations of the Australian people. How the Voice operates can also be changed by future parliaments. What they can't change is the existence of the Voice. Only the Australian people would be able to do that - through another referendum.

Voice proponents say formalising this way for Australia to listen to Indigenous voices is more important than the removal of discriminatory clauses from the constitution (which 91 per cent of Australian voters supported at the 1967 referendum) or the insertion of formal words of recognition in a preamble (which Liberal leader Peter Dutton has proposed for a future referendum if this one fails).

Vote "yes" if you think our country will benefit from listening to Indigenous communities through a formal mechanism - the Voice - that can provide meaningful and honest advice because it is protected from politicians and bureaucrats.

Vote "no" if you think putting the Voice in the constitution is too much of a change to our system of government when we already have a Parliament to make decisions for all Australians.

Doesn't this just divide Australians?

As signatories to the Uluru Statement from the Heart put it: "In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard".

Proponents of the Voice say the question being asked in the referendum is not about race but about recognising the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in Australia before 1788 and giving them active and ongoing input when laws and policies that affect their lives are being devised and enacted.

Because the Voice would comprise only Indigenous Australians advising only on matters that concern Indigenous Australians, Voice opponents say it is divisive, dividing Australians by race.

Indigenous activist and lawyer Noel Pearson says it's wrong to conflate race and indigeneity, which is defined as originating or occurring naturally in a particular place: "This is not about race. This is about us being the original peoples in the country. It is not inequality to recognise that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were the owners of Australia since time immemorial, it is simply the truth".

Vote "no" if you do not want to amend the constitution to include a body that speaks for only one group of Australians when the constitution should belong equally to all Australians.

Vote "yes" if you want Australia to make a meaningful step towards reconciliation by recognising the world's oldest living culture in the constitution and empowering First Nations communities to take control of their own destinies and future.

Aren't Aboriginal people represented in Parliament already?

Australia has a record eight senators and three members of the House of Representatives who identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. They represent parties across the political spectrum and come from every state and territory except the ACT. They are: Senator Dorinda Cox (Greens, WA); Senator Patrick Dodson (Labor, WA); Senator Jacqui Lambie (Independent, Tas); Senator Kerrynne Liddle (Liberal, SA); Senator Malarndirri McCarthy (Labor, NT); Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price (Country Liberal, NT); Senator Jana Stewart (Labor, Vic); Senator Lidia Thorpe (Independent, Victoria); Linda Burney, Barton MP (Labor, NSW); Dr Gordon Reid, Robertson MP (Labor, NSW); Marion Scrymgour Lingiari MP (Labor, NT).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders make up three per cent of the Australian population and are a minority in nearly every electorate, so while an electorate may choose an Indigenous MP, Indigenous communities don't have the power to elect someone to represent them. The Voice would allow them to choose representatives from their state, territory, region or remote community to provide the Parliament and executive government with advice on ways to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in areas such as health, education, housing and employment.

Vote "yes" if you think the Voice will help Parliament and the Government better address the unique challenges that Indigenous communities face by allowing those communities to say what works and propose solutions based on their own lived experience.

Vote "no" if you think the Voice gives Australians who identify as Indigenous in effect two votes to be able to influence matters of federal government policy that affect them when everyone else across our multicultural nation gets only one vote.

What about Indigenous people who oppose it?

Like all Australian communities and cultural groups, Aboriginal communities are diverse and it's not surprising that there are different priorities and different views.

The "Yes23 campaign" points to polls indicating that more than 80 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people support the Voice as a way for their communities to present better information and more accurate insights to decision-makers so they can deliver better outcomes for Indigenous people.

"No" campaigners such as Jacinta Nampijinpa Price argue that while no one expects Indigenous Australians to think the same or have the same priorities and policy positions, we are being asked to put in place a Voice that speaks for all of them.

Vote "no" if you think the Voice has the potential to divide Australia by making constitutional recognition of our First Peoples conditional on enshrining extra powers for one group.

Vote "yes" if you think the Voice has the potential to unify Australia by formally recognising our First Peoples in the Constitution and helping to address the problems of racism and Indigenous disadvantage.

Why isn't there more detail?

There is. In July 2021, the Indigenous Voice co-design process report by Professor Marcia Langton and Professor Tom Calma recommended the advisory body be made up of a gender-balanced 24 members serving four-year terms, including two from each state, territory and the Torres Strait Islands; five representing remote communities; an extra representative for mainland Torres Strait Islander people, and two optional members jointly appointed by the Voice and Government.

But Melbourne University's Associate Professor Partlett says we aren't voting on a detailed proposal at the referendum because that isn't how our constitution works.

"What we're doing is voting on an idea," he says. "The detail will emerge through legislation after the Australian people decide 'yes' or 'no' whether they want to create this institution in the first place."

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese says that a joint parliamentary committee co-chaired by Labor and Coalition politicians would "oversee the development of legislation for the Voice advisory group".

Vote "yes" if you believe the Voice is needed because decades of government policies haven't helped us "close the gap" between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, and we need to try a different approach.

Vote "no" if you believe that we don't need more government cost and bureaucracy when we already have a federal parliament to make decisions in the best interests of all Australians.

Update: This article has been amended to more clearly attribute sources: voice.gov.au, referendumcouncil.org.au, ulurustatement.org, liberal.org.au, fairaustralia.com.au, yes23.com.au, aph.gov.au, humanrights.gov.au, The Conversation